To the Filipino people, who dramatized in the Battle of Mactan on April 27, 1521, their rejection of a foreign tyranny sought to be imposed by Ferdinand Magellan, that they may soon recover lost courage and, with greater vigor and determination, rid the Philippines of the evil rule of a home-grown tyrant with the same initials.

A dedication by Primitivo Mijares, 1976

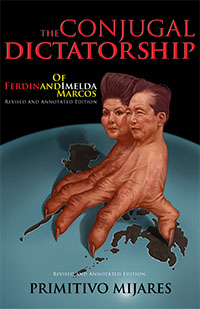

The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos provides a detailed, first-hand account of the Marcos administration during the era of Martial Law. It was written by the only person Ferdinand Marcos trusted with open access to his personal chambers: press secretary and right-hand aid Primitivo "Tibo" Mijares. Unlike other books about the era, this book was written by a true insider who took no steps to "sugar-coat" the details, even those which resulted in his self-incrimination.

The book was originally published in 1976, at the outset of Martial Law. The book, and Mijares's testimony in the United States congress, inevitably led to the death of Primitivo Mijares himself, as well as his youngest son, Boyet Mijares. In 1986, the book was republished and was one of the driving forces behind the EDSA revolution. Since then, the book has been out of print. The only commercial copy which remains is the one you can find on Amazon. While they didn't change the text at all, the formatting makes the already newspaper-like work even harder to read.

Now, a revised and updated edition of The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, with additional references, citations, and new content has been released. Order your copy of the hardbound version of the book online here. The paperback version is available at National Bookstore.

Liliosa Hilao was a 21 year old activist for academic freedom, and editor of Hasik, the official newspaper of her school. She was the seventh child of an impoverished fisherman from Bulan, Sorsogon. She was murdered two weeks before she would have graduated summa cum laude at the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila. During the first quarter storm of 1970, she became a democrat, joining the Demokratikong Kabataan (Democratic Youth Alliance), formerly called Aletheia. Despite her family's impoverished state at the time, she, together with other activists, worked in the slums of Intramuros, helping the squatters with their basic needs.

She was tortured, raped, killed, and her body was returned bloodied, mutilated, and scorched with muriatic acid.

In April 4, 1973, 15 men and a woman alighted near the Hilao residence in Project 3, Quezon City. These included Col. Felix, Lt. Castillo, Lt. Garcia, Sgt. de Sagun, George Ong, another man named Felix, and a Women's Auxiliary Constabulary (WAC) named Ester. The rest of the group positioned themselves about 20 meters away, presumably in case anybody escaped the residence.

Together, they ransacked the apartment while Liliosa's mother, her youngest sister Gigi, 16, and the second-youngest daughter, Marie, watched in horror. Her mother was even in a plaster cast, recovering from an unrelated accident. Ester held Gigi in one room, two of the other men held Marie in another room.

Miraculously, Marie managed to escape, leaping over high concrete walls, past howling dogs, and ignoring warnings from the two men that she would be shot. Gigi, on the other hand, was not so lucky. The men, furious at the escape of her sister, brought Gigi back to camp Crame, before returning her to her home again at 6 PM. One neighbor realized what was happening, and attempted to warn Lily before she got home. Unfortunately, Liliosa was still capture and brought back to her residence.

Liliosa's cries echoed through her neighborhood until well past 1:30 AM. A loud, desperate, and anguished scream could be heard as Lt. Castillo undressed Lily, who kicked and fought the entire time. Tension spread throughout her neighbors, who were anxious to help but knew that there was nothing they could do. Lily struggled so hard, for so long that the rape attempt at their residence ultimately failed. Instead, they brought her back to Camp Crame, handcuffed.

All of this happened in the span of a single day. In following day, there was no news about her, and her family was under heavy surveillance for the time being. Lily's cousin Arnold was tortured so severely that he couldn't work the next day.

April 6, 1973 was the last day Lily was seen alive. Gigi was summoned by the WAC to supposedly bring clothes for Lily. Gigi was held for the entire day, and allowed to return home on April 7. She brought home a placard saying "Sister is dead."

When her body was returned to the family, Lily's skirt was torn and bloodied, her torso covered with bandages, and her underclothing completely missing. It was clear that she was re-clothed after her death. Nobody knows what happened to Lily at Crame except the guards who were there, but the V. Luna Hospital holds records of her autopsy. Her face, especially her mouth, was scorched by muriatic acid. Her neck and throat were badly burned. Two pin punctures were found on the arm. In an attempt to prevent an impartial autopsy, the internal organs were removed. Hypodermic needles were jabbed into the arms to make it appear as if she was a drug addict. Her eyes and mouth were wide open.

Before her burial, the military attempted to fool the students by hiding Lily's body. Of course, seeing her body would reveal the awful nature of her death. Her body was taken out of a coffin and placed in a stretcher, purportedly for re-autopsy at the Funeraria Popular. They tried to hide it in the basement for the meantime, planning to transfer it elsewhere, but a group of students were on the way to the Memorial Center at the time. The guards shuffled to get near the body, but they were driven away by angry students who formed a human cordon around it.

The military gave three conflicting versions of her death.

Fortunato Bayotlang was a salesman for a pharmaceutical firm in Davao. His story was relayed to Primitivo via a letter sent through the missionary order, which has a mission in Mindanao. The identity of the author, as well as his religious order, were withheld for obvious reasons.

Dear X,

In August, I began an assigned 6-week language review to acquire some polish and get the unknowns to fall into place. During this time I became involved in a case involving the Tagum constabulary police and Davao pharmaceutical firm salesman, Fortunato Bayotlang.

Fortunato was beaten to death by the constabulary security unit - apparently a case of mistaken identity, and his two younger brothers, Fernando, 15, and Ruperto, 8, were imprisoned. They had been accompanying Fortunato because it was Saturday, and they had no school. I was asked by the Association of Major Religious Superiors to photograph the deceased and gather evidence for them two days after the incident occurred.

Two days more passed, and I became concerned for the welfare of the two younger brothers, still imprisoned in the Tagum stockade. I gathered members of the Justice and Peace Commission of Bishop Regan had attempted to get them released, and/or find out what the military charges of subversion consisted of. They had been released overnight to attend the wake and funeral of their brother, under armed escort, so we found them at their family home and humiliated the guard to get him out of hearing range so we could talk to the boys.

Fernando, obviously relieved and happy to see us, told of six plain- clothesmen curbing his brother's company car, taking them to the PC compound and interrogating them. Fortunato was handcuffed behind his back and continually punched enroute to the stockade while being asked over and over, "Where is Dodung?" (This is the only question they ever asked any of the three). At the compound, Fortunato was taken to a small shed less than 30 feet behind the command post building. The two younger boys were manhandled by two men in a parked car less than 10 feet away while three men "cared for" Fortunato.

"Father," Fernando told me, "Fortunato screamed, begged, pleaded - and his last words were 'if you are going to kill me, or must kill me, please shoot me because I've done no wrong.' Also, the men mauling him came out three times in blood-soaked clothing to get more 2x2's because they were breaking too easily." This - in spite of the fact that the Bayotlangs are civilians, and there was no warrant on file, no identification of the arresting officers, no "bookings," no civil liberties.

A doctor in a cell over 50 yards away, upon hearing the screams and seeing the bloody clothing, threatened to file charges against the military unless Fortunato was taken to the Davao Provincial Hospital of Tagum. There, he was administered first aid, and a hospital employee told me, "We have no facilities. Father, for a man who has been that badly mauled." Three hours later, he died of "subdural hemorrhage caused by severe beating to the head and the whole body," according to the coroner's report.

During this same period, Fernando was being taken by his captors to see Fortunato at the hospital. A detour was made through a banana plantation, and he was tied "spread eagle" around a tree. He was then beaten with clasped, clenched fists, jabbed with a rifle butt and barrel, and struck with a pistol. This is part of a "tactical investigation" - no, not for a commando - for a 15-year-old boy.

At present, Fernando is frightened by all strangers, and physically runs from them. He also continually extends and retracts his tongue unconsciously - the result of another "tactical investigation" where his tongue was repeatedly pulled, beaten against his teeth, and burned with cigarettes. He now lives with Brother J. C., MM. in Sigaboy to allay his anxiety.

The case of Fortunato Bayotlang and his brothers was thoroughly investigated by the Police Constabulary and the Department of National Defense because Bishop Regan and Maryknoll would give them no peace. Military findings were that there is a case, and warrants for arrest have been issued, but none of the six Constabulary Security Unit members have been apprehended, although they have been frequently seen loitering in the market place. The only ordinary Police Constabulary involved was Fernando's mauler, who was demoted. When I told Fernando the demotion was given for the constabulary's "indiscretion," he replied: "If that's what an 'indiscretion' is, I'd hate to see what a 'mistake' looked like."

These, and other stories like it, as well as documents and other evidence of the atrocities committed during Martial Law can all be found in the book. Click on order above to order now.

Release Date: February 20, 2017

This is the hardbound version of the book. The paperback version is available at National Bookstore.